A Spin of the Wheel

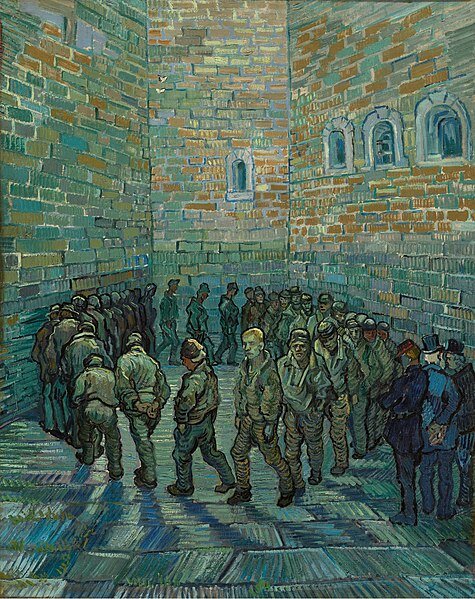

“The Prison Courtyard” by Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

Tanner glanced at the clock on the wall, and then back down to his plate. He frowned.

It was almost 6:30. A Spin of the Wheel would be on at 7, and the only thing standing between himself and the show was the violent green stain of broccoli taking up far too much room on his plate. The ham was gone. The mashed potatoes were gone. The broccoli was not gone, and he’d let it get cold, which was a mistake, he realized now, just like dad said it would be. He’d let the broccoli get cold and now he wasn’t allowed to watch A Spin of the Wheel until he finished it.

No one else was even at the table – his mom was on the phone in the living room and his dad was doing his share of the dishes. He’d taken that long to finish dinner, which was pretty much par for the course when his mom made broccoli. Broccoli sucked.

Roscoe nudged at his elbow, a cold, wet dog’s nose in his lap. Tanner looked down, into the retriever’s liquid-dark eyes. He could give Roscoe the broccoli. Roscoe liked broccoli, actually. It grossed Tanner out.

But the last time he’d done that, he’d been caught. They’d grounded him from A Spin of the Wheel for weeks afterward. And he really didn’t want to miss the show tonight. Andrew Collingshire, 21, of Irondale, had made it through the past few rounds, even when no one thought he would. He didn’t have any points. He’d been a Contestant a long time. Everyone at school talked about how he might win this season, or at least get sponsored out. And Tanner wanted to see what happened. If Collingshire got sponsored it out, he wanted to be there for it.

He sighed, speared a healthy mouthful of limp broccoli with his fork, and raised it to his lips.

Davey was still asleep on the trailer’s pockmarked couch when Amanda Esgrove, 27, of Irondale, slipped inside. Out of habit, she went to check her phone to see what time it was, but she didn’t have it, of course – taken as evidence in the criminal case and all that – so she glanced at the clock on the stove in the trailer’s kitchen. It read 9:37 a.m., which meant Davey was more than late for whatever job he happened to be holding now. Or “holding.” She’d been gone a few months. She wasn’t at all sure he was still employed.

She kicked through a nest of beer bottles on her way to the couch, hoping the noise would wake him. It didn’t.

She shook him, and while he snorted in his sleep, he still didn’t wake up.

Jesus fucking Christ, she thought, and had to keep her eyes from flitting to the end table at the couch’s arm. She had wants – fuck that, she had needs, actual real, fucking needs she’d felt as an ache deep in her marrow while she puked in a stained, reeking toilet in jail and her skull hummed with the infuriating buzz of withdrawal – and, on that table right there, Davey had everything she needed to turn that ache into one, stupid hot air balloon and send it far, far away over the horizon of her mind.

She breathed deep and looked away. Supposedly, there was a class or two you took in jail to get you ready for this sort of temptation. She closed her eyes and tried to think about what the teachers of those classes would tell her now, if they could see her.

They’d tell her to go somewhere else, probably because that was the next option on their flowchart, where all the colors stayed in the lines. Esgrove didn’t actually have anywhere else to go, and that wasn’t an option on their flowchart, which had always looked more to her like a boardgame than anything else.

She shook Davey again, and this time his eyes opened, bloodshot and stupid-looking.

“Davey,” she said.

“Esgrove,” he said, in a sleepy, hoarse voice. “Aw Esgrove, you’re back.”

“Yeah,” she said. “I am.”

This was a bit passive aggressive, she knew, to leave it at that, and she knew she wasn’t supposed to be passive-aggressive; the counselor in jail had told her not to be this way.

But she was also, plain and simply put, pissed. Really fucking pissed.

Not that it mattered, because Davey didn’t pick up on the hint.

He pulled his phone from the pocket of his jeans.

“Damn,” he said. “I’m late for work.”

“You still have a job?” she asked, and she knew that was a loaded thing to say too, but she didn’t really regret saying it either.

He sat up, actually awake, she sensed, for the first time since she’d walked in. “Yeah, Esgrove, I still have a job. I wasn’t the one who got arrested.”

She pursed her lips, but was proud of herself because all she said was, “No, you weren’t.”

He swung his legs off the couch and kicked a few of the stray beer bottles away himself. She heard him pad down the hall to the trailer’s back bathroom then, around the toothbrush in his mouth, he yelled, “So what’s your deal? Someone bail you out or what?”

This was too much. She could actually hear herself snap, and there was an image that went along with it – herself, a 9-year-old Girl Scout on a camping trip, pulling a branch the girth of her arm around a tree trunk until, with a thunderous clap, the thing splintered and came apart and she tumbled backwards into the dirt, the tree’s gnarled roots digging into her shoulder blade.

She stood from the couch and stormed to the bathroom, where Davey was spitting toothpaste-foam into the sink.

“Nobody fucking bailed me out,” Esgrove said, realizing she was yelling only after the words were out of her mouth. “You hear me, asshole? Nobody fucking bailed me out. I got sentenced. That’s how long this shit took. I was in jail for months and I couldn’t even get ahold of you for most of it.”

He spit into the sink and then turned to her, eyes still stupid with the hangover; he was only beginning to register what she was saying, she could see. “Esgrove I…I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to…I just didn’t have any cash and I was –“

“You didn’t even call,” she said, and then she felt the wave break within her, the one whose approach she’d been watching for a long time, feeling in the back of her throat, and she finally let it go as the tears leaked through her eyelashes and down her cheeks. “You didn’t even write, Davey. I was…I was in the pool for The Wheel.”

He had, at least, set his toothbrush down and spit into the sink. Then he turned to her, to embrace her.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t know.”

His embrace didn’t really mean anything to her by this point – if he’d paid attention, at all, he would’ve known she was in the pool for the wheel; how could you miss it these days? – but she was too tired to shove him away and keep yelling at him by now. All she wanted to do was pass out on something other than a springy jail cot reeking of piss and rubber.

She closed her eyes against the tears and hugged him back.

Charlie greeted Sam in the jail’s back parking lot, where the deputies parked, and offered her a gloved hand in the evening’s gathering gloom.

“Sam,” he said. “Good to see you again.

She accepted his handshake – her slim hand disappearing in the vastness of his mitten – and did her best to remain diplomatic.

“Good to see you too,” she said, as they trudged across the parking lot through a few inches of wet snow. The storm showed no signs of slowing up, and by the time she was done with The Wheel, she thought, the roads would be hell. She was covering this shift for Mason, and she suddenly saw herself home right now instead, curled up with a cup of tea and whatever show Derrick happened to have on, watching this snow fall through the windows instead. It made her jealous as well as guilty she was out here doing this instead.

“How’s work been?” Charlie asked. “It’s been a minute since you were on The Wheel.”

By design, she thought.

“Work’s been good,” she said, as he pulled his issued key card from the pocket of his slacks and held it up to the keypad to the side of the jail’s massive metal back doors. They stepped inside, stomping their boots free of the snow and sleet on the rug just inside the Commerce County Jail’s back lobby. She did not want to talk to Charlie about work. She hated his involvement with her work, even tangentially, as a TV news anchor – all his Twitter shout-outs were just a bit too friendly and too often, and she didn’t want sources she respected to think she associated more than she had to with this sort of unctuous bottom-feeder.

“I saw you had the Sunday front page last week,” Charlie said, as they made their way to the sign-in desk, where a rotund deputy had his muddy boots up on the tabletop, rolling a toothpick between his lips as he scrolled through his phone. “Totally upending the gubernatorial race with that scoop about the treatment of campaign staffers. That was a good story.”

“Well shit,” Sam said, as they signed in and stepped through the metal detector next to the desk (Charlie’s metal tie pin set off the alarm, but the deputy didn’t even look up). “You know I live for your approval, Charlie Harding.”

He laughed his big, booming laugh, loud enough to confirm her suspicion he was still too stupid to take this as the fuck-you it was.

“I always approve of your stories. I’ll miss working with you when you’re done at the paper.”

“We’re late,” she said, nodding in the direction of the stage.

“Well gee, I guess we are,” he said, as they started down the blank cinderblock corridor to the studio stage. They came to the first heavy metal door – painted a nauseating institutional green – and waited for the deputy in the command room at the jail’s center to unlock the door for them. It was more time with Charlie Sam had never asked for. The heavy gunshot-crack of the lock’s release, when it came, was a welcome sound. Then they were walking down more hallways and through more doors, passing others (marked C Pod, where the women lived; G Pod, where the men lived; S Pod, where the crazies lived, unaware [or perhaps they were!] of the headlines Sam penned about them) until they came to an antechamber padded in soundproof material. To Sam, it had always looked like this room had been papered with giant foam egg cartons. A slim, wooden door waited away to their left. They passed through, to backstage.

This was the studio added onto the jail when the county first rolled out A Spin of the Wheel two years ago. They’d sliced the rec yard in half to do it – that was before Sam’s time at the paper, but she’d read the stories. There was always a waiting list for tickets to watch The Wheel, and every week, at about 6:30 p.m., the deputies shut everything down while they escorted the crowd through the jail hallway and to this very back room. The difference was the crowd entered through a massive set of gilded double doors about 50 feet further down.

The door she followed Charlie through belonged only to the hosts of the show, of which she was one. Unfortunately.

There were the sound crew guys, the makeup people, the tech and visual media kids – all the usual suspects Sam remembered from her last time hosting The Wheel. She remembered them well. What she’d forgotten – what she always managed to forget – was just how much these last few minutes leading up to showtime actually sucked.

As they took a seat behind the massive gleaming desk with the mockup of the Irondale skyline behind them and The Wheel – 10 feet across at least – to their left, Charlie looked over at her and smiled.

Tanner did actually finish his broccoli in time to watch The Wheel. It was close, because he also had to do his share of the dishes, but he managed it. He hopped up onto the couch between his mom and dad just as the theme song ended and the lights were coming up on the stage.

There was Charlie Harding, in his big, glittery suit, flashing his big, glittery grin beneath a gel-slick formation of hair bearing vague resemblance to a cliff Tanner had seen on a family vacation to Yellowstone over Summer Break. Next to him was the lady from the newspaper, but he couldn’t remember her name.

“Good evening Irondale, happy Thursday night, and let’s thank God for – what exactly?” Charlie Harding asked.

The studio crowd cheered in one leviathan voice, “Tomorrow’s Friday!”

“Yeah, that’s right it is, isn’t it?” Charlie asked, as Tanner felt a giddy sense of peaceful happiness rise from deep within his gut. Tomorrow was Friday! No school the day after tomorrow! He could sleep in! He could play videogames or basketball or read or do nothing at all, and no one could tell him otherwise! And he had a whole episode of Another Spin of the Wheel to enjoy first!

“…and tonight I’m also here with Sam Prill, our very own crime reporter from the Irondale News, who hasn’t been on the show for quite some time,” Charlie said, nodding to the woman sitting at the desk next to him. “Let’s hear it for Sam, folks, and our partnership with the Irondale News.”

Only some people clapped at this, Tanner noted.

“She never looks comfortable,” his mom said.

“No, she doesn’t,” his dad agreed.

“I kind of wonder why they have her on here sometimes,” his mom said. “They need that other reporter, that bigger guy with the glasses…”

“Oh yeah, I know who you mean,” he said. “The sports reporter…Mason. His name is Mason.”

“Yeah,” his mom said. “Let’s get Mason back.”

“…down to three contestants at this point, after Ruby Dickenson, 32, of Fenlowe, was sponsored out,” Charlie was saying on the TV, Tanner noted. He remembered Dickenson getting sponsored out. He was kind of sad, but kind of happy too, because he thought Dickenson had been pretty. A very rich woman who worked in the Capitol Building had sponsored her out of the show on the last episode, he remembered. The very rich woman had said she’d been touched by the video of Dickenson crying about her dog dying while she was in jail. The very rich woman had wanted to help her, so she’d paid for Dickenson to leave the show.

“That leaves us with Wes Wheeler, 38, of Fenlowe; Isabela Ruiz, 30, of Green Rock; and Andrew Collingshire, 21, of Irondale,” Charlie said, stretching the last syllable out into a stadium announcer’s pronunciation IRON-DAAAAAAAAALE as the crowd exploded into a cacophony of boos and cheers.

Tanner sat up and scooted to the edge of his seat. His big toes just about brushed the floor from here. Not everybody liked Collingshire, because he was going to become a SEX OFFENDER once he was sentenced (if he was sentenced, Tanner remembered), but Tanner liked him. Other people did too, and they’d tried to sponsor him out, but SEX OFFENDERS cost more money to sponsor out, so it hadn’t happened yet.

Tanner thought Collingshire was kind of cool. Collingshire was tough. Collingshire was smart. He was what Tanner’s dad jokingly called the “strong silent type.” When they showed clips from the jail where people got into fights or used bad words (always bleeped out), Collingshire was never included. Kids at school sometimes pretended to be Collingshire. Tanner’s best friend Jimmy actually used a notebook with Collingshire’s face printed on it when they did Free Writing in school. Jimmy said Collingshire was a “badass.”

Tanner’s dad thought Collingshire was a thug, and he always called him that. Just a thug. Or a loser. And you couldn’t be anything worse than a loser, living in your parents’ basement. Tanner knew this for a fact.

“Let’s take a look at how each contestant spent their week in the Commerce County Jail, shall we, folks?” Charlie asked, as the screen went black, and the footage began to roll from within the jail.

Esgrove lasted longer than she thought she would before she got high again. She’d left the trailer and gone for a walk. She’d called her mom on Davey’s phone but, as expected, her mom hadn’t picked up. She’d walked to the motel down the street, to see if she could afford a room there, away from Davey. She couldn’t. So she’d told herself she would just go back to the trailer and have a chill night and get up early tomorrow. She was supposed to meet up with her probation officer at 10 a.m. after all. If she could make it until then, things would probably be OK.

She didn’t make it until then, of course. She hadn’t really expected to, nor had anyone else. In the end, Esgrove did what Esgrove did, and got blasted. Davey had the dope right there on the table all afternoon. She felt it on the surface of her mind as a burning, sweat-soaked itch, a scab begging to come off, one she could only resist scratching for so long.

One hit, she thought. Just one. Just one. Just one. I can do just one and show up sober tomorrow.

So she’d done just one hit, and the sense of weightless carelessness – better than sex could ever hope to be – smacked her full in the frontal lobe and made her weak at the knees, and she’d sat down on the couch and actually laughed, suddenly sure everything would be OK.

Just one more. Just one more. Just one more.

When she awoke, Charlie Harding was on TV and Davey was on the couch next to her, a beer in his hand, laughing. They cut to Collingshire on the screen in grainy black and white footage from the jail, trying to hold a conversation with someone who believed he was Buffalo Bill.

“Yeah, but I’m a cowboy, baby,” the man said, across the jail cafeteria table from Collingshire. “These soldiers took me hostage, but I’m gon’ break out and tour the Wild West. ‘cause I’m a cowboy baby.”

Even under the studio audience’s laughter, Esgrove could hear Davey himself laughing. She blinked – slow, heavy blinks – and realized she knew that voice and those words coming from the TV. That was Fred Stanley, 54, of East Bank. He’d given her a book, “One Hard Blue, Colorado Sky,” on her first day in jail.

“Annie Oakley gave it to me just before the soldiers got to us,” he told her, eyes wild, focused on some point above her left shoulder. “Those soldiers at the door, they don’t know I’m gon’ break out of here and tour the Wild West. ‘cause I’m a cowboy baby. Now you get this book back to me, you hear? That was Annie Oakley’s favorite book, and it still smells like her, and I got to give it back to her when I break out.”

She read the book and she liked it. It reminded her of her dad. She’d told Stanley that when she gave it back to him and –

She bristled, suddenly, against her drugged stupor. Had any of that made it onto this episode of The Wheel? She’d never been a contestant, but she had been in the pool for the show, and anyway, people seemed to like to laugh at Stanley.

People, of course, including Davey.

He set his beer down and turned his head in her direction.

“Hey Esgrove,” he said.

“Davey, what the fuck,” she said. “Why are you watching this?”

“Watching – oh,” he said, and shrugged, as the screen cut to a one-on-one with Collingshire, one in which he talked about his kids. “I’m sorry, it was just on. But you should’ve seen this dude they had on here – he was full-on convinced he was Buffalo Bill, it was hilarious –“

“I know,” she said. “I knew him in jail. He gave me a book.”

“Really? Damn, was he crazy then too? What was he like? Was it funny?”

“No, Davey, it wasn’t funny at all,” she snapped, and her anger burned hot and pure and sliced through her high like hot water through bacon grease. “It was jail. It fucking sucked.”

He was silent a moment, and sipped his beer, but she watched his gaze return to the TV screen.

The clip of Collingshire talking about his kids ended and the screen cut back to Charlie Harding and the woman from the newspaper at the desk.

“And once again, folks, we’d like to thank you for being here tonight and for watching – thanks to A Spin of the Wheel, the Commercial County Jail is the only jail in the country taxpayers don’t have to pay for, and also the only jail the country earning a profit,” he said, as the usual polite applause rippled across the audience. “We’ll be back after these good people take this time to offer you their goods and services.”

The show cut to commercials.

Sam leaned back in her chair and rubbed her eyes with the heels of her hands as they cut to a commercial break. They were getting closer to being done, but that meant they were getting closer to spinning the wheel too. She hated that part more than anything else. More than talking about what the jail inmates (contestants, she reminded herself) had done to land them here. More than watching the footage of the inmates (contestants) filmed without their knowledge in the jail, meant to titillate the crowd with all its ugly raw drama. More than fielding calls from the rich fucking assholes who declared they’d been touched by God and were moved to sponsor someone out of the show. Not bail them out of jail, mind you, just out of the show.

Take them out of the running for death. Or, to use the euphemism of the show, The End Game.

Because that’s really what all this was about, not that anyone wanted to talk about it. It was about death. About monetizing the death penalty, turning it into a fucking game, and it wasn’t polite to bring it up in conversation, but there you had it. The Commerce County Jail had become a money machine because everyone who served time there found themselves in a lottery for The Wheel and every six months, if you were one of the unlucky 13 inmates picked to be on the show, you very well could wind up dead at the end of it all, regardless of what you were in for. You “won” the show if you were one of the last two inmates (contestants), but not the one who was selected to be put to death. Winning didn’t get you anywhere. It didn’t help your criminal case. It just meant you weren’t put to death and you wouldn’t be considered for future seasons of the show.

Of course, you could also be compelling enough, just by going through your daily life in jail, to get someone to sponsor you out, which usually cost hundreds of thousands – or even millions – of dollars. The jail didn’t care about who got sponsored out even if the viewers did – it was still money in the bank, after all.

The scheme was so successful other counties were looking at duplicating it across the country. Over the past two years, the Commerce County Jail had snagged a spot on just about every national newspaper and news magazine, and none of those stories were unflattering – the jail was, after all, not costing taxpayers a dime. It was actually earning them dimes – and actually, more than just dimes. Along the way, A Spin of the Wheel had become the most popular TV show in the Northwest and had secured primetime contracts for the next five years.

When Sam suggested to her editor she write a story questioning the ethics of putting people to death to fund a county government, her editor had given her that weathered old basset-hound look so common to an ancient gentleman of the press, and told her not to look into it. Not because the Irondale News endorsed the practice, of course, but simply because there was no controversy about it. Who, her editor asked, was really going to criticize the system?

The people in jail for starters, Sam had said, without much hope.

Yes of course, her editor had told her, offering only the mournful basset-hound look to soften the truth, but who else?

The correct answer was “no one else,” and Sam knew that. It didn’t placate her though. Just pissed her off more.

“What do you think?” Charlie asked her.

She blinked and looked up with only a weak hope he’d realize how much she hated his presence this close to her. Or on this show. Or this fucking planet.

“What do I think about what?’Charlie laughed, as if this were a clever quip instead of an honest question. “About the show. Do you think Collingshire is going to get sponsored out? There’s the extra sex offender fee, but after that clip I don’t know. He’s pretty popular.”

Sam blinked at him as if he’d suggested they converse with a goose about this upcoming election. “I…don’t really…want to weigh in.”

There was that laugh again. God, she was going to knock him out right here on primetime TV. She wished for a moment Derrick watched The Wheel just so he’d see her do it. The ring he’d given her would slice this gasbag’s fat fucking lip clean open. “Ever the hardworking ethical journalist. That’s good.”

Is it, Charlie Harding? She thought but did not say.

“Thirty seconds,” she heard one of the tech guys say into the earpiece they wore on the show.

She rubbed her eyes one more time – careful not to smear any of the stage makeup, although she could feel it beginning to flake off at this point under the heat of the stage’s lights – then sat up at the glittering desk once again to get ready for the commercial break to end.

The crowd burst into another round of prompted applause as Charlie Harding sat forward and flashed his big, dumb grin right into the camera.

“Welcome back Commercial County, welcome back, and thank you once again for joining us here at the Commercial County Jail, where we are just minutes away from – you guessed it – a spin of the wheel,” he said, and waited for the next set of applause to die down as well. “We are down to three contestants, one of whom will be taken out of the running for The End Game by a lucky spin tonight. Once again, we have Collingshire, Wheeler and Ruiz and – what’s that?” He asked, putting a finger to his earpiece for effect. “Do we – I’m told – yes – I’m told we have a sponsor for Ruiz, folks.”

A gasp went up from the audience. A sponsor for Ruiz! That left only two contestants! And still a spin of the wheel to go! This was it!

Sam sat back in her chair once again as the tech kids let Charlie talk to the sponsor, some preacher at a megachurch somewhere, who wanted to help “connect Ruiz to resources” because it was obvious “she never had a fair shot at life.”

“Absolutely, of course, of course,” Charlie was saying. “Now sir, you are aware of the extra costs to sponsor a contestant this late in the evening and this late in the show, correct?”

“I am,” Sam heard the man say, and his voice was piped into the studio as well. “But you know what? I am OK with that. I have a check for $1 million ready to go right here. Let’s get her off the show.”

There was a thunderous wave of applause at this and Charlie made a show of having to yell over it as he raved something about the “wonderous generosity,” of the megachurch preacher.

“It’s just something I felt called to do,” the man said.

“That is truly amazing, truly amazing,” Charlie said, and tied up the phone call.

Then, to the waiting audience: “Ruiz is now sponsored out of the show. You know what that means, folks?”

More applause and cheering. Sam had never been on the show when the mood was this pitched. She thought of a pack of starved dogs.

“That’s right,” Charlie said, and she imagined him as a Macy’s Day Parade balloon, just inflating at all this excitement. “That means we will, tonight, know who has been selected for The End Game. There’s only one thing left to do, and I think you know what that is.”

In a single, terrifying voice the crowd chanted SPIN…THE…WHEEL.

Away to Sam’s left, a spotlight stirred awake and illuminated The Wheel on a stand, ten feet across or more at any given point. Its surface bristled with hundreds of tiny light bulbs, and right now, the wheel was evenly divided between red and green light bulbs. Each inmate (contestant, Sam reminded herself, they’re not inmates, of course, they’re contestants) had an assigned color. When there were more names, the wheel was divided into a large pizza of colorful slices, but those slices vanished as the weeks wore on and people were either sponsored out or eliminated from the running. Now, with Ruiz gone, they’d pulled her color – yellow – from the wheel, leaving on Wheeler and Collingshire’s colors. Collingshire was green; Wheeler was red.

A teenage boy – he couldn’t have been more than 15 or 16 years old – stood near the wheel, ready to spin it. He had the stacked build of a football player, and it was only then Sam remembered he was, indeed a football player – some kid the sports section had done a big feature on a few weeks back, who was having a career-making season. That made sense. Everyone wanted to spin the wheel – got to get your 15 minutes of fame in, and all that – and so it was usually some sort of hometown hero who got to do it. The last time Sam co-hosted the show a decorated firefighter had spun the wheel, a reward for saving 14 senior citizens from a burning nursing home.

The boy held a tablet in his hands and Sam knew – because the Irondale News had run enough stories about the show in its entertainment section – there were two buttons on its screen. One button made the wheel spin; the other made it stop. It didn’t stop instantly, of course, which meant there could be no biased influence on the part of the person spinning the wheel – it was just about impossible to predict how long the wheel would spin after you pushed the STOP button on the tablet.

As the crowd settled into an expectant silence Sam felt deep in her gut, the football player turned away from the wheel and tapped the tablet.

Just as the wheel didn’t stop all at once, it didn’t start all at once either. Sam watched as it made one lazy spin, and then another, and another, ticking past the brass piece of metal at the top of the easel on which it was perched with a sound like playing cards in the wheel of a bicycle. Then the wheel’s rim became an orange-brown blur, and she could no longer track its movement with her eyes. The kid let it spin for about 30 seconds or so, and then he tapped the tablet again. The wheel slowed, and she was once more able to pick out the two colors – green, red, green, red, green and red. It kept slowing over the course of what felt like an agonizing 10 minutes but could not have been more than 10 seconds.

Then it stopped in the green portion of the wheel.

Green was Collingshire’s color. Which meant he was no longer on the show.

“Ladies and gentlemen we have a contestant selected for The End Game,” Charlie said, but the crowd didn’t need him to say it. They could see for themselves. The roar was deafening.

Sam shifted in her chair, wishing she was anywhere else right now.

“Dang,” Tanner said. “I really thought Collingshire was going to get sponsored out.”

His mom ruffled his hair and smiled. “So did I,” she said.

“That was probably the best season of The Wheel so far,” his dad said, watching the cheering crowd on TV. “I can’t believe Ruiz got sponsored at the last minute like that.”

He stood, stretched, and yawned. “All right, sport. We let you stay up late for the show, but it’s time to go to bed now. Tomorrow’s Friday but it’s still a school night.”

Tanner sighed, then stood from the couch himself. Tomorrow was indeed a school day, but he didn’t even care at this point – all he wanted to do was talk to Jimmy about the surprise ending of The Wheel. His friend was going to look stupid now carrying around a notebook with Collingshire’s face on it, Tanner thought. ■

Ethan Szarleta isn’t a starving artist, but he does need food badly. He lives in Boise, but grew up north of Denver, was doomed to be a writer from a young age and has been on the losing end of that tumultuous relationship ever since. While he wants to examine the American criminal justice system through the lens of science fiction and horror, he understands other people do that as well, and is ready to quit writing about it at a moment’s notice if the concept becomes too popular.